Thinking Like A Watershed Study Guide ©Johan Carlisle 1998 ©Johan Carlisle 1998 |

||||

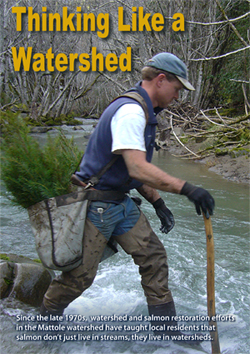

SUMMARY OF THE FILM AND THE ISSUES It is safe to say that almost everyone lives in a habitat that has been damaged by modern industrial life. The extent of that damage varies greatly – urban areas are mostly developed for human living and working, while suburban areas often retain some of the characteristics of the pristine landscape. Rural communities usually look the most like the original landscape, and can still support the plants and animals that were part of the original ecosystem, unless the land and rivers have been damaged by careless logging, mining, agriculture, or other human activities. As awareness of environmental issues grows, more people are becoming aware of the extent of the damage done to their local environment. As they start asking questions about why the natural landscape around where they live is the way it is and how it got that way, the question eventually arises: What can be done about it? When a wave of “new settlers” – part of the back-to-the-land movement in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s – moved to the Mattole valley, they noticed that the native salmon were rapidly dwindling. They started asking government officials, local old-timers, biologists, and other experts what was going on These new settlers were mostly activists from the cities looking for a quiet, clean place to build a small cabin and raise vegetables and kids. They applied their activist skills to trying to save the salmon. First, they built innovative streamside hatchboxes to raise baby salmon to supplement the dwindling wild stocks. But the salmon populations continued to decline. The new settlers became aware that salmon don’t just live in water, that they need certain types of places, known as habitat. And they found out that what the earlier settlers called the valley was called a watershed by scientists. The plant and animal communities live together in an area of land, all of which drains into one river and affects the salmon habitat. Ecological restoration is a growing movement worldwide. More and more people are taking responsibility for the care and stewardship of their natural environment and learning how to “think like a watershed.” |

||||